Why fairywrens sing to their eggs

Superb fairywren moms teach their unhatched babies a vocal password to distinguish them from cuckoo intruders.

Hello, everybody!

Thanks for joining me for this new post for Beaks & Bones.

Quite a few new subscribers have found their way here lately via me sharing my drawings for the Inktober art challenge. Thank you and welcome! I’m glad you’re on board.

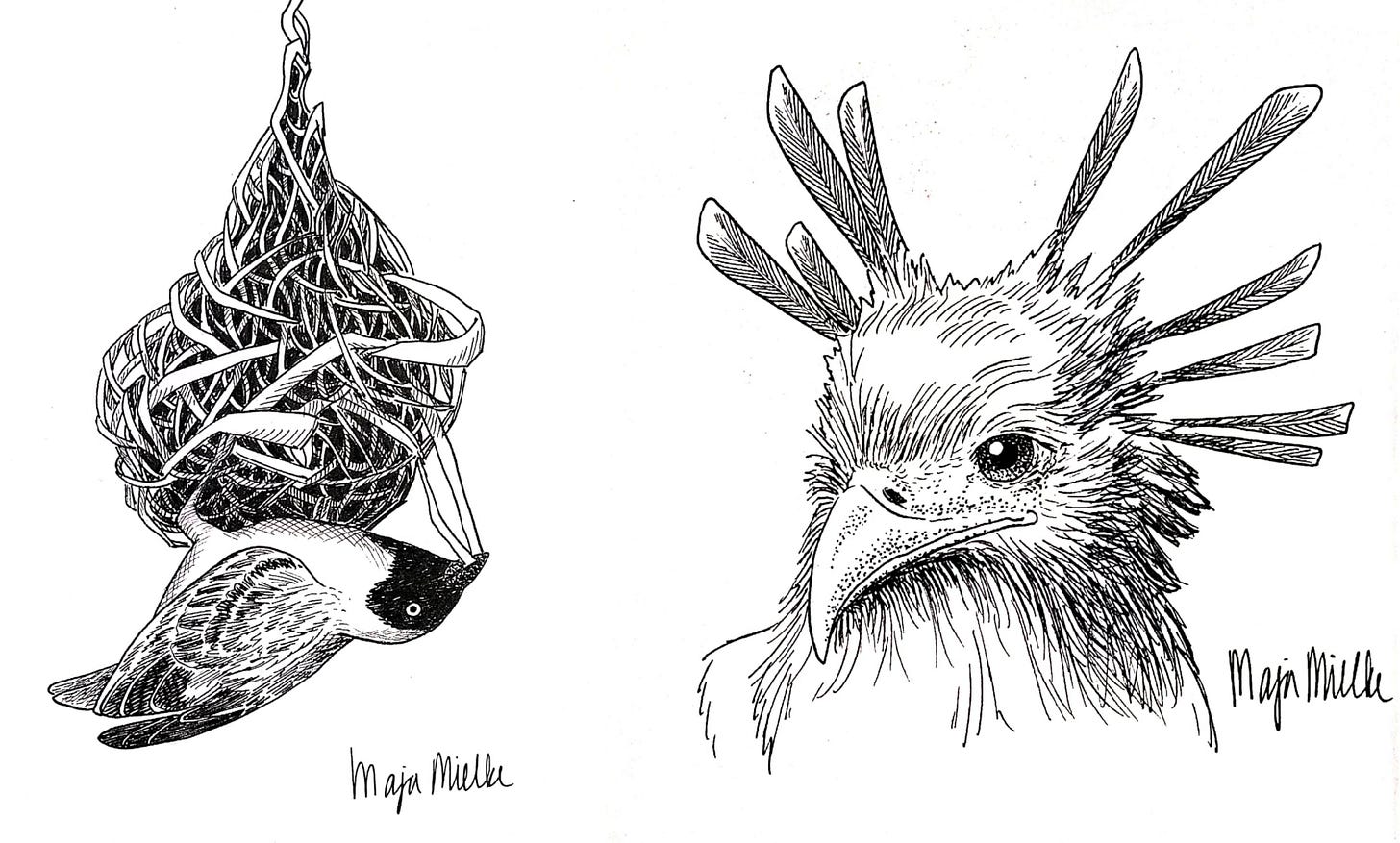

I’m a researcher and science communicator, and in this newsletter I’m sharing fascinating science facts about birds. My nature art is normally not a focus in this newsletter, but I have the impression that my art resonates quite a bit with the readers of Beaks & Bones.

Which is why I wonder whether I should share more of my art in future editions of this newsletter. What do you think?

Thank you! Ok, now let’s dive into today’s topic.

Why fairywrens sing to their eggs

The cuckoo nestling is now alone in the nest of its host parents. Within two days of hatching, it has kicked the fairywren chicks out of the nest to claim all parental care for itself—opening its wide beak and trying to imitate the fairywren begging calls. One day later, the fairywren parents abandon the nest and begin a new brood.

Superb fairywrens (Malurus cyaneus) from southeastern Australia are common hosts of the Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoo (Chalcites basalis). A study from 20121 found that fairywrens sing to their eggs, teaching their unhatched young a vocal password that says, “I’m a fairywren, I’m your chick!”—a password that cuckoos fail to reproduce.

For their study, the researchers mounted microphones in nests of Superb fairywrens, recording their calls during four breeding seasons. They observed that the ‘incubation call’ that females sing to their eggs contains a signature element unique to each mother. The begging calls of their hatched young closely imitated their mom’s signature call.

To test whether the chicks had actually learned these calls rather than producing them intuitively, the researchers shuffled eggs among nests at the start of incubation. They found that the young mimicked the signature call of their foster mom rather than that of their biological mom. This was evidence for embryonic learning—they had actually learned the calls before they hatched!

Potential cuckoo intruders in the wren nests tried to imitate their host’s signature element as well—with less success. Their imitation of the call was so poor that the parents abandoned the nest as soon as the cuckoo was alone in the nest and started vocalizing.

The researchers concluded that the wren parents distinguish their offspring from a cuckoo by the accuracy of the signature call. The call serves as a form of vocal password that helps fairywrens avoid investing valuable resources in raising a chick that is not theirs.

Now you might ask, “But if the wren embryos can learn the password during incubation, why can’t the cuckoo?”

It’s because the cuckoo doesn’t have enough time to do so. Female wrens start singing to their eggs ten days after laying. Their chicks hatch about five days later—five days during which they’re exposed to the incubation calls of their mom. A cuckoo, however, hatches just two days after the mom starts calling—much less time to learn the password.

The researchers suggest that this may be the reason the females wait ten days to start calling to their eggs—to make sure that a potential intruder doesn’t have enough time to learn the call.

Have a wonderful rest of the week! All the best,

Related posts from the archive:

No cuckoos allowed

Redstarts adjust their nests to make them less appealing to cuckoos.Birds form long-term ‘friendships’ to help each other raise their young

Superb starlings in Kenya show that cooperative breeding is not limited to close family members.Birds in same-sex pairs successfully rear chicks

Same-sex partnerships in birds provide direct and indirect benefits for both individuals and whole populations.

Wow, what a cool study! I'm always amazed at the creativity of researchers. This is such an amazing example of the evolutionary arms race between parasite and host. Thank you so much for sharing this story with us. I love that there is still so much we're learning about nature's creatures. Although, I do admit to a bit of sorrow for the blameless cuckoo chick left abandoned...

That is so fascinating! Thanks for sharing, just another reason to love these cute little wrens :)