Owls can look to the left by turning their heads to the right

The anatomy and specialized function of their neck vertebrae allow owls to perform head rotations of 270 degrees.

Time flies! This is already post no. 10 of Beaks & Bones. It’s great to have you on board! If you’re a more recent subscriber, and would like to take a look at my previous posts, you can browse the archive here:

Wait—is that the owl’s front or back? The way the bird rotates its head around reminds me of the droid R2-D2 from Star Wars. The owl is now looking at me, but is it looking forward or backward? I have to look twice.

270 degrees. That is the amount of head rotation that owls are able to perform. That is three-quarters of a full rotation—which basically means, they can look to the left by turning their head to the right. Why would an owl do such a thing? To improve their hunting success: an immensely mobile neck helps them to fixate their prey during nightly hunts, compensating for the immobility of their large eyes.

An owl’s neck is made of 14 vertebrae, twice the number of a human neck. But that number alone doesn’t make it hyper-flexible. What is so special in the anatomy of the owl’s neck that allows for such incredible head rotations? In 2017, researchers from Germany published a study1 showing that the secret of success lies in two characteristics of the neck in owls: 1) a division of labor between different parts of the neck and 2) the added rotations of individual neck joints that allow high rates of rotation because of their special anatomy.

The researchers created a digital 3D model of the neck of a North American barn owl (Tyto furcata pratincola), consisting of all 14 individual vertebrae connected by joints. Based on this model, they could test how much rotation each joint allows for without the neighboring vertebrae colliding. The results were then matched with x-ray video recordings of living Barn owls turning their head. Here’s what they found.

1) Bending of the lower neck

Let’s start with a little demonstration. I invite you to look up from your phone or computer screen and balance your head on your neck and look forward. Don’t move your eyes, just stare forward. Now drop your left ear towards your left shoulder. This bending of the neck results in a tilt of your head, but without moving your eyes, you’re still looking forward. Now, raise your head again and then drop your chin to your chest, your gaze facing down. Your neck is now more horizontally aligned. Now, from this position, perform the same bending movement as before. Your neck and head will tilt out towards the side like a water tap, and you will be able to see the floor to your left. Notice how, even without moving your eyes, part of your left and backside is now within your field of vision. This is what the lower part of the Barn owl’s neck (consisting of the lower 5 joints) does to initiate head rotation. The important difference is that the owl’s lower neck is aligned horizontally by nature, but the head still stays upright because of the S-shape of the neck (see image below). The sidewards tilt from this bending of the lower neck is responsible for a slight shift of the head relative to the body in head rotating owls.

2) Rotation of the upper neck

Ready for another little exercise? Again, start with balancing your head on your neck and look forward. Now, while keeping the head upright, look to the left as if you were looking at a person sitting next to you. Notice again how, without moving your eyes, parts of the left and back come into your field of vision. This twist of the neck is what is done by the vertical upper part (the upper 5 joints) of the owl’s neck.

In the digital 3D model of the Barn owl neck, rotations of up to 40 degrees in a single joint of the upper neck were possible. Why is that not feasible in the human neck? Because our vertebrae have much larger articular processes (zygapophyses), which limit the movement between adjacent vertebrae.

Adding up all joints of the 3D model revealed a total head rotation of more than 300 degrees. This, however, disregards the presence of surrounding soft tissue, such as muscles and ligaments, that may restrict the rotation in real life. When testing manual neck rotations in dead Barn owls, however, the researchers could confirm these incredible results: rotations of even more than 360 degrees were possible without rupturing muscles or ligaments! This, however, does not necessarily prove that 360 degree rotations are also possible in live birds. Indeed, these large rotations in dead specimens resulted in a strange twist of the neck that started to collide with the shoulder. Probably nothing that a living owl would do. But still!

3) Special vertebrae anatomy

OK, so we have bending of the lower neck and a twist in the joints of the upper neck that allow for impressive head rotations in Barn owls (the middle part of the neck contributes rather little to the total rotation). But let’s come back to the soft tissue. How is it possible that the spinal cord is not squeezed? How are the arteries not torn? The answer again lies in the anatomy of the neck vertebrae: the diameter of the wide central canal and the arterial canals are larger than the spinal cord and arteries passing through them. This provides enough room for these vital tissues to stay safe during head turns.

That’s it for this week’s post. If you liked what you read, please consider subscribing and tell your friends!

Have you seen owls in the wild rotating their head around? I haven't had the luck to observe these birds in their natural habitat so far. My observations have been limited to visits to the zoo. But I can’t help it—whenever I see an owl, I wonder: where’s the front side?

Have a wonderful rest of the week! All the best,

PS: Next week, I’ll be on vacation. I’ll take a short break from publishing this newsletter. But I’m looking forward to sharing more fascinating bird science stories with you very soon. Thanks for sticking around!

I saw owls in March first time and it was something incredible, like magic - those magnificent creatures just sitting on the tree near their nest...

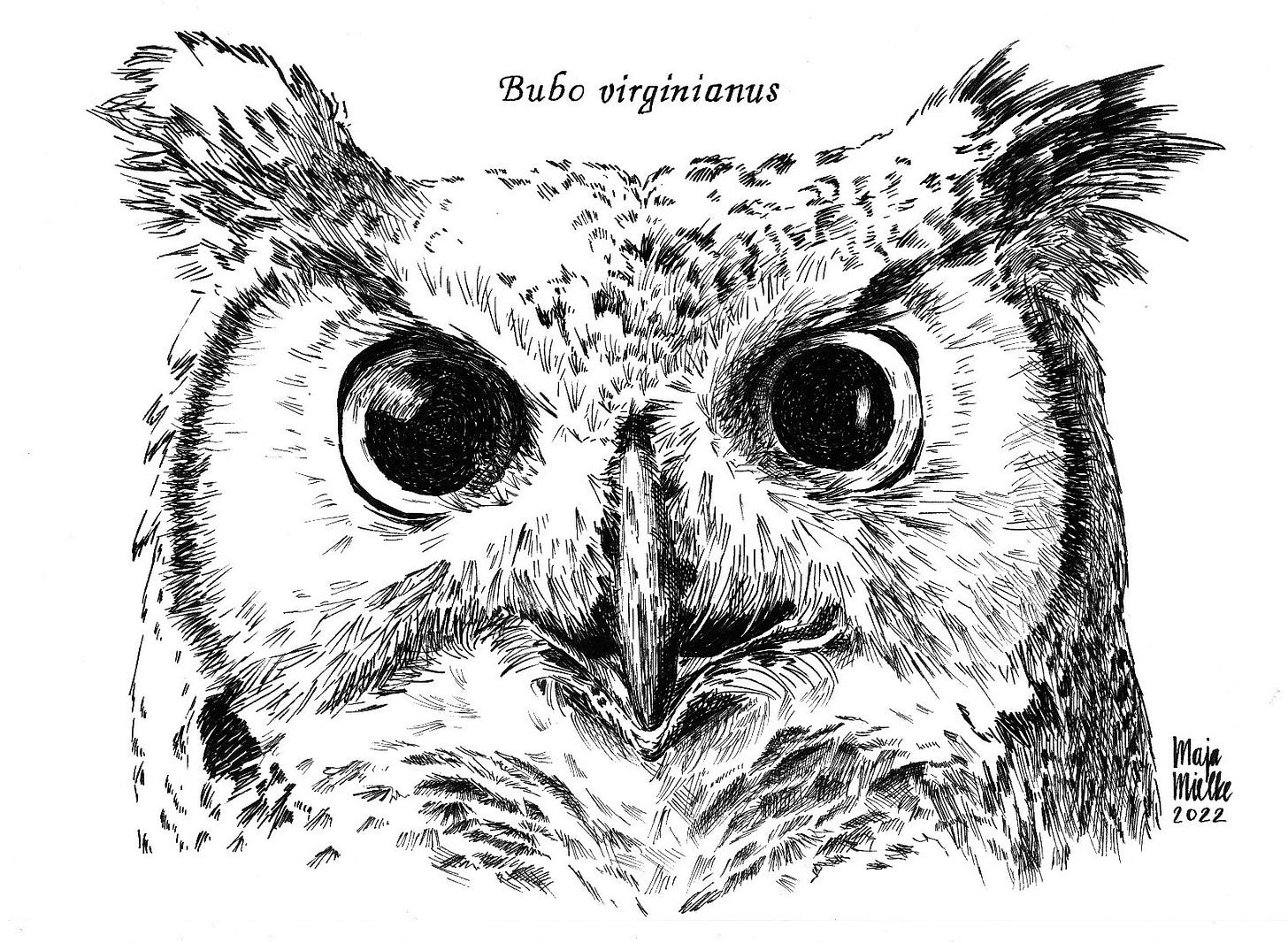

Absolutely fascinating, Maja! And your pen and ink Great Horned Owl is so lovely!