Why do woodpeckers not get stuck in trees?

Well, they actually do get stuck in trees quite often—but they free themselves within a blink of an eye. Here's how.

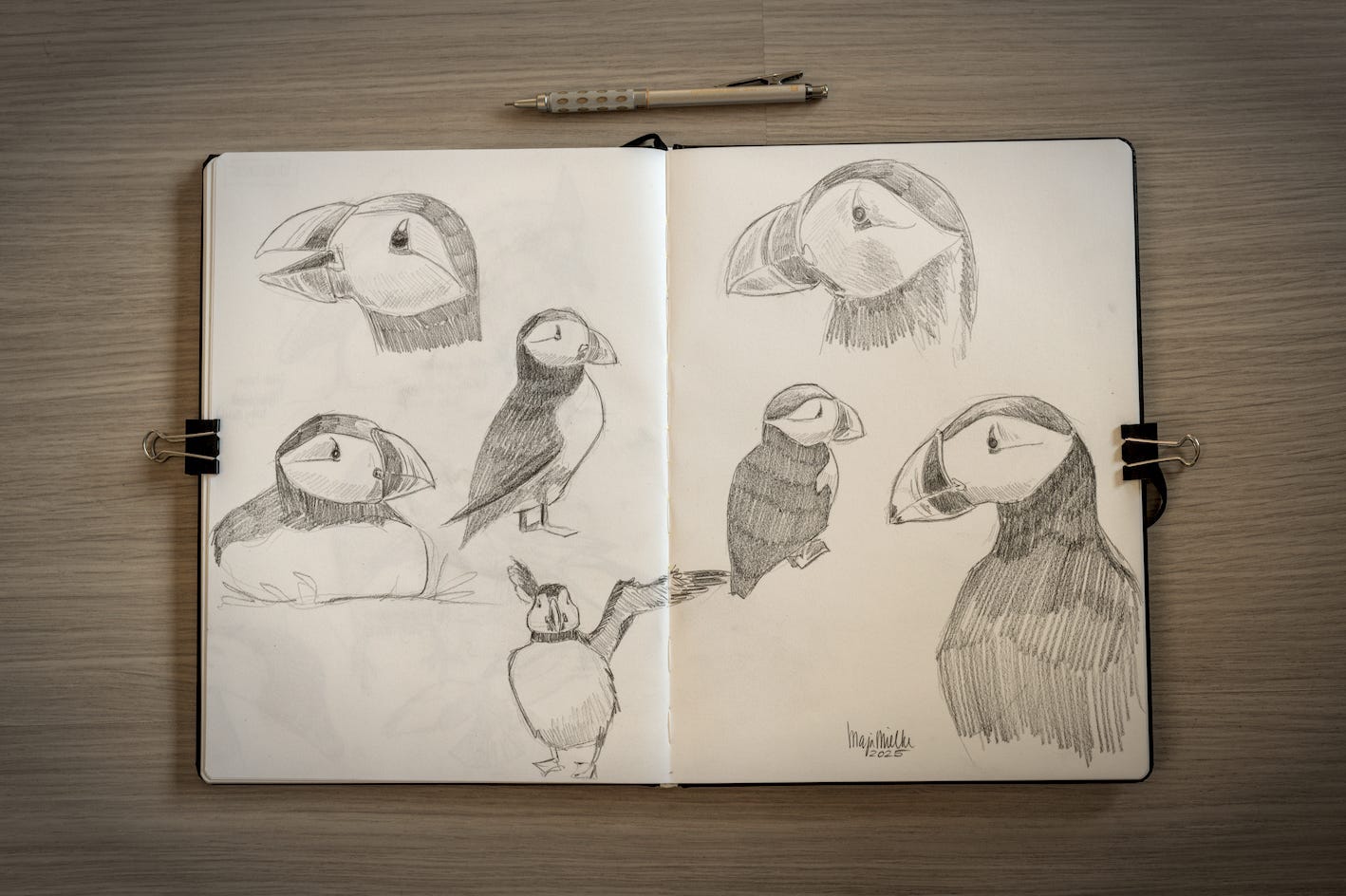

Thanks to everyone sticking around and to all the readers who recently subscribed to Beaks & Bones. I’m very much enjoying this journey so far and looking forward to sharing some fascinating bird research with you once again today. If you have missed my last post on Puffin fledglings, you can read it here.

Today, we’ll do the name of this newsletter justice. We’ll do so by taking a closer look at the beaks and bones of one of my favorite groups of birds—woodpeckers!

Let’s get started!

Woodpeckers drill their beaks into trees up to 12,000 times a day at speeds of up to 25 km/h (ca. 16 mph). Letting those numbers sink in, you might wonder:

How do they never get stuck in trees?

Well, they do get stuck, actually. But why then don’t we ever see woodpeckers hanging with their beaks on tree trunks, struggling to free themselves? The answer lies in the incredible anatomy of bird skulls, which allows woodpeckers to free themselves within 50 milliseconds!

For this study1, I didn’t have to look far—my PhD supervisor published this research in 2022. He and his co-authors recorded high-speed videos of pecking black woodpeckers (Dryocopus martius) in zoos in Austria and Switzerland. Out of 284 analyzed pecks, the birds got stuck 103 times, unable to retrieve their beak directly after the impact. But the videos showed that the birds immediately freed their beaks by performing a series of very subtle movements. Have a look:

(Video source: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.243787)

The skull of a bird is not a solid body. It’s highly kinetic, which means that the different bones of the skull are not fused, as in humans, but can move relative to each other. Two of these bones are the upper and lower jaws, which can both move relative to the skull and slide along each other. Woodpeckers make use of exactly these movements to free their beak when it gets stuck.

Woodpeckers release their beak by conducting two very subtle movements.

In the first phase, they lift their forehead up. Because both upper and lower beak tips are stuck in the tree, and because of the kinetic skull, this causes the beak to open slightly at the base (you can see a small gap appearing in the video above). At the same time, the upper jaw slides backward a bit, freeing the tip of the upper beak.

In the second phase, the whole beak is rotated downwards (the head is lifted), which causes the retraction of the lower beak tip.

Et voilà! The beak is free!

This entire freeing mechanism, as complex as it might seem, takes no more than 50 milliseconds. In fact, it is impossible for us to recognize with the bare eye that it was stuck in the first place. A woodpecker could perform 3 pecking-and releasing cycles within a second.

The kinetic skull, it turns out, is an essential feature for woodpeckers that doesn’t compromise but complements their pecking. In fact, by ‘wiggling’ their beaks free instead of pulling straight back, they save enormous amounts of energy.

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading Beaks & Bones. If you liked this post, please consider subscribing or sharing it with a friend.

Have a wonderful rest of the week!

All the best,

PS: Look what I made after writing last week’s post and being in puffin-mood for the whole week:

that's incredibly interesting! also makes me feel sorry for those poor kingfishers I see online getting stuck in trees beak first :( glad to read that woodpeckers have a solution

Now that’s interesting! So happy there are science-minded folk (aka scientists) on this platform. Learning so much. Love the drawings too!